Helyszín címkék:

Two geniuses in one family

DunakanyarGO

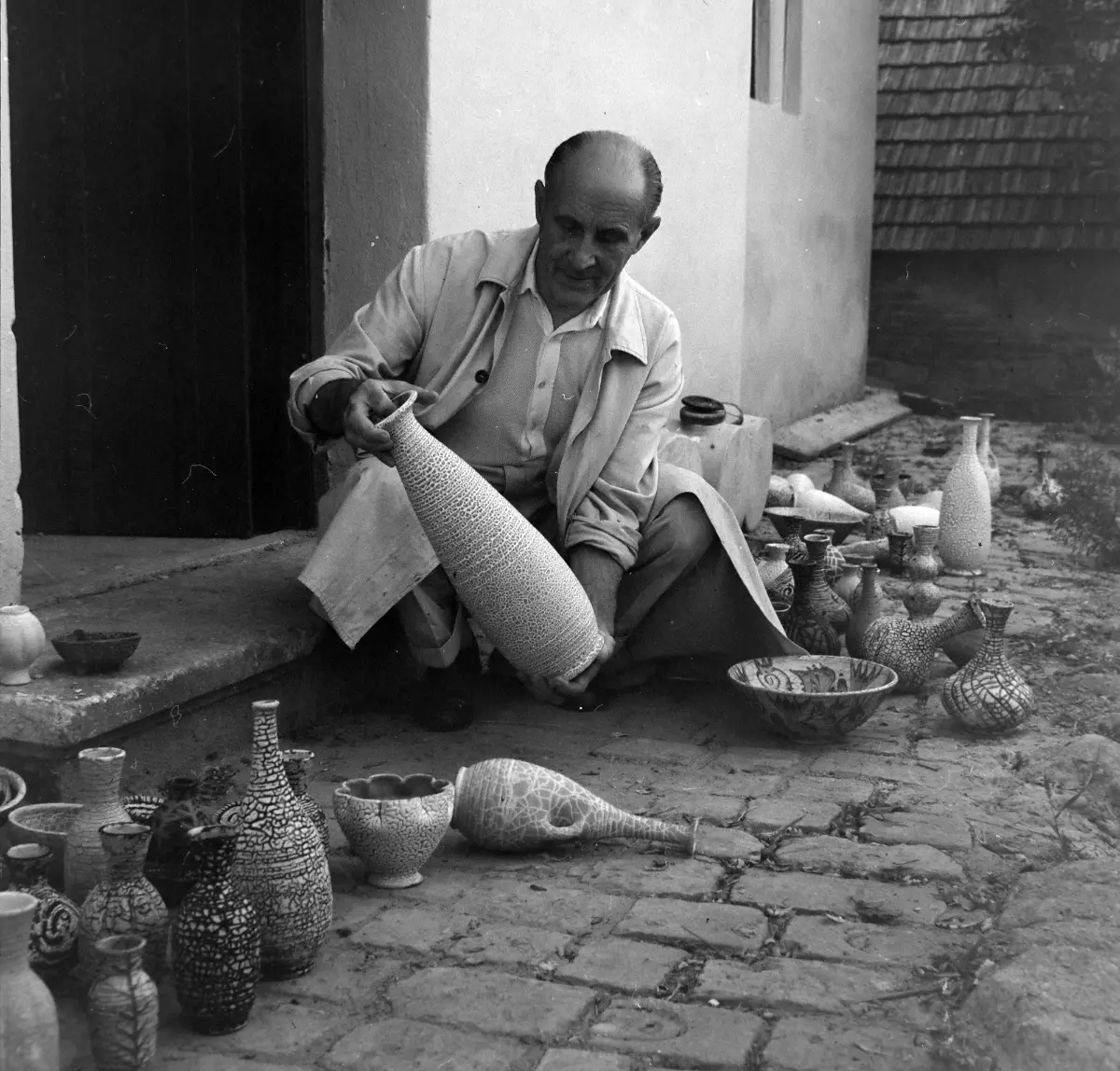

The Danube Bend could never become isolated: the river and the trade routes have resulted in people coming and going for thousands of years, and some of them have been stuck here. Settlers arrived on boats here, while at other times dreamy artists decided that the area would be ideal for creating their works. Géza Gorka, who was born in 1894 in Nagytapolcsány, in the territory of today’s Slovakia, was an artist, but he did not come here to dream but to work. However, Verőce captivated him – he was active there until his death in 1971, beyond his work, he also added a great deal to the life of the village with his intelligence. Many people start working with clay for a living, but Gorka learnt to paint from 1910. According to contemporary reports, he was not short of talent, but he soon fell in love with the formable raw material provided by the earth – he came to Mezőtúr to the potter, Balázs Badár, where he mastered traditional Hungarian folk art technology. With this massive basic knowledge, he migrated to Germany where he was learnt about industrial ceramics and types of enamel for two years in the workshop of Paul Mann and Max Luger.

He came to Verőce because of work: Floris Bank house set out to create a modern company and he was asked to lead the technical work. He believed that at Keramos S.A. he could combine the German maiolica style, the technology of glazed pottery, which had been introduced by the Anabaptist Hutterites expelled from Switzerland, namely the Haban Christian sect, with traditional Hungarian pottery. Everything went well for the first few years, but after a change of ownership in 1927, professional differences developed, so he left to start his own business.

He knew that one of the most important conditions for development is to have a good measure of oneself: From 1928 he regularly exhibited at the domestic and foreign exhibitions of the National Society of Applied Arts. The fact that his works still appear all over the world at international auctions is partly due to the fact that he entered his ceramics at almost every major art event abroad: He won a silver medal at the Milan Triennial of Applied Arts in 1933, but he also appeared in the 1934 World Expositions in Brussels, in 1937 in Paris, and in 1939 in New York. He continuously improved, he was looking for new technologies of glazing, created new shapes with his hands. Modern, foreshadowing works came out of the kiln in Verőce – he drew from Hungarian folk art, and from the Haban industry or from Chinese porcelain, however he felt it necessary, so that all his works became recognizable in the style of “gorka”.

The 1930s gave the Danube Bend an amazing cultural effervescence: writers, artists, painters were Gorka’s guests, heated debates and friendly conversations made the years before the impending war idyllic. Unfortunately, soldiers did not understand his art at all: when he could finally return to his workshop, he was welcomed by tens of thousands of cartridge cases and broken pieces of earthenware. As soon as the Second World War was over and the kilns of the Zsolnay factory in Budapest were heated, he was there to start the series production of ceramics fired at a temperature of 1200 degrees with László Mattyasovszky – however this artistically and industrially exciting task was interrupted by nationalization, so Géza Gorka returned home to Verőce and started all over again. In addition to articles for personal use, he made more and more works of art from the clay of Börzsöny. He received the Munkácsy Prize in 1955 and the Kossuth Prize in 1963. His daughter, Lívia, secretly passed the ceramic master's exam. After his father had learned that she also chose this career, he tried to support her to find her own form language. It seems that he was also a good mentor and master, as Lívia Gorka was successful in the international environment, and just nine years after her father, she also received the Munkácsy Prize.

The museum in Verőce is a perfect place to understand the geniuses, as the pottery of both the father and the daughter can be admired here. The cosy villa and the small manicured garden are sunny, south-facing, where in the house, which used to house the kiln, there is now a great cultural café, the Zsengéllő, that awaits guests with a cup of coffee or a delicious bite to eat under the trees, after visiting the museum.

Source (photo): Fortepan/Bojár Sándor, Fortepan/Kotnyek Antal